No story sits by itself. Sometimes stories meet at corners and sometimes they cover one another completely, like stones beneath a river.

Mitch Albom

The story you’re about to read fits neatly alongside and under many others with great complexities, but I am going to pull this one away to itself, and appreciate a time I spent alone with my dad on a cross-country trip to start a new life, again.

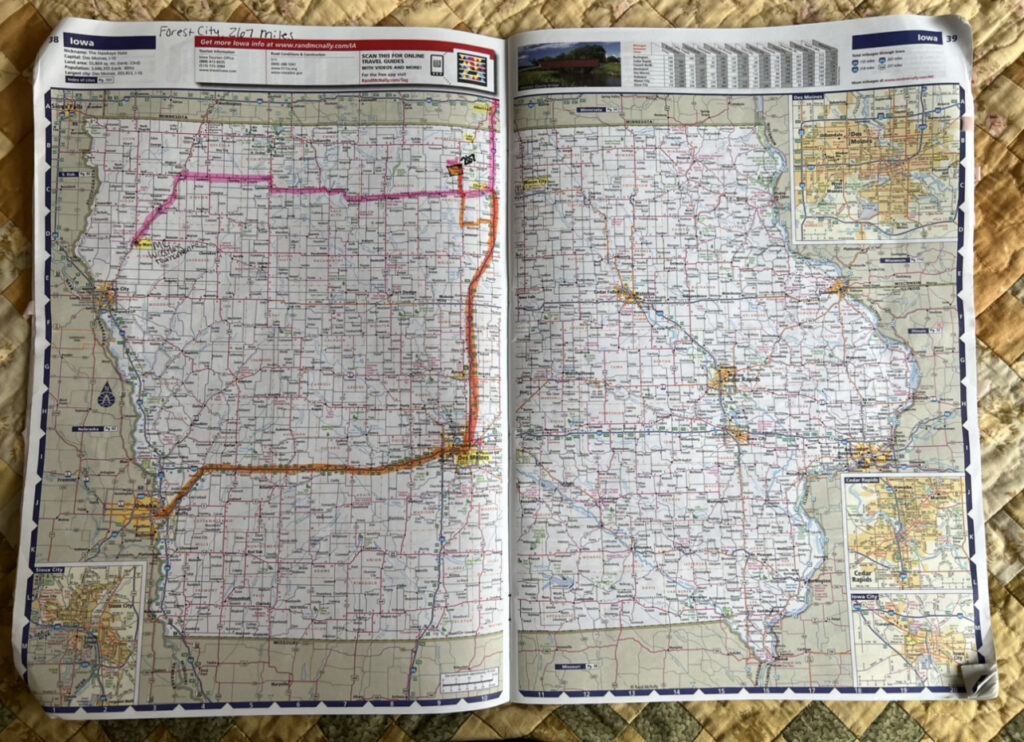

June 18th, 2015. My dad pulled into Forest City, Iowa. We’d spend five days together on the road to California. Me, alone with my dad. It took a minute to settle in, but as we drove it was like all of a sudden we’d left everything else in the past. The only baggage in the truck was what I took with me to my new life.

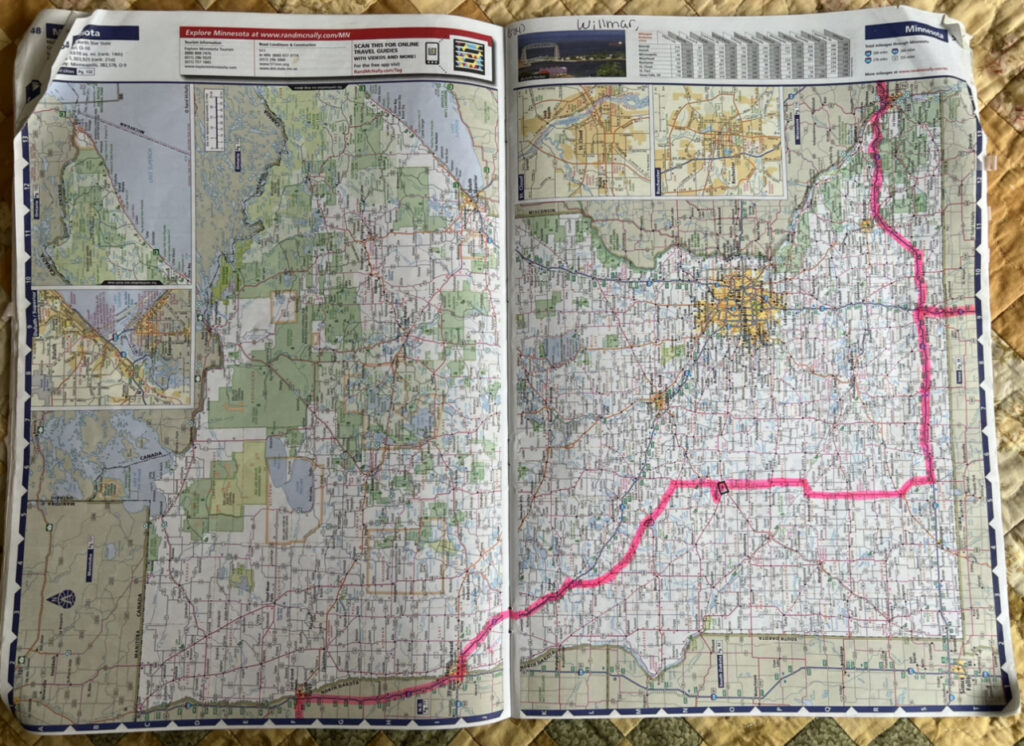

The first 500 miles led us from Forest City to Willmar, Minnesota. By the time we packed everything in the Yukon it was mid-afternoon and we needed to get on the road and start somewhere. I feel like the first day there was more surface level conversation than any other day—I can’t think of a time we’d ever spent a substantial amount of time alone together, and we didn’t really know each other anymore outside of sharing accomplishments and the loop of I’m proud of you’s I pulled out of him in his own language. When you leave for college and become someone else your parents don’t really know who you’re becoming unless and until you reintroduce yourself over and over again as you grow.

We were comfortable the rest of the days. I remember mostly the quiet, just being together. I love that about people who get you. I was observing everything outside and everything about how he just was as a human, my dad. I learned a lot about him just by being with him, and I learned that I am a lot like him, too. He’s a really curious guy. We’d be passing something random and I’d listen to him go, “I wonder . . .” and then he’d go on and on. I do that all the time. I wonder about things. One of the other things I think I picked up on as well is that, like me, he likes quiet. He likes to think and let his mind wander to how things are working, or about nothing at all. It’s one of the things I most remember respecting about him as a young girl—how did he know everything about everything?

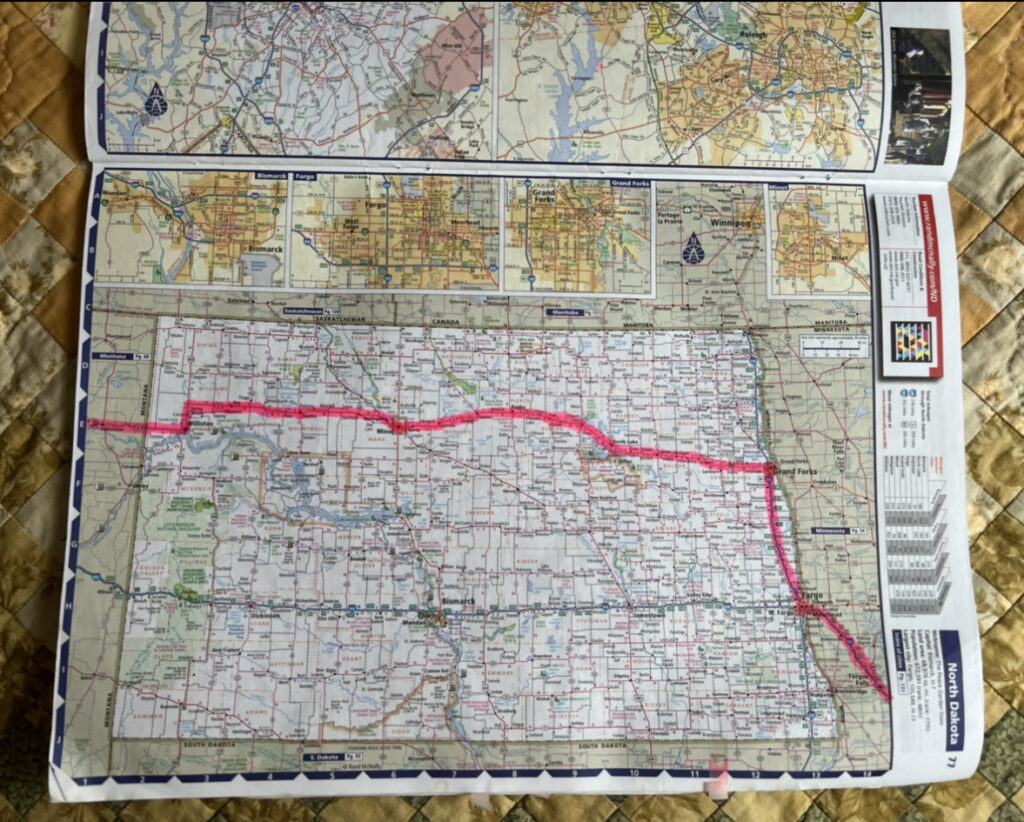

On the second day we crossed into North Dakota around Fargo. That was the first time we switched off a highway I knew, 94, to 29 up to Grand Forks and then kicked it west once we hit highway 2. He told me this was the only way to road trip across to California so I was expecting immediate grandeur and excitement. Turns out that North Dakota is super boring. I remember going through Rugby, because it’s the geographical center of North America and we explored there a bit. I also remember, from along the entire route, the multitude of different and interesting water towers and post offices. I love small town post offices. They remind me of a very straightforward time, a time that makes sense. There’s so much undeveloped land, and it’s gorgeous. I was already in love with mountains and flatlands, but I was enchanted by and fell quickly for bridges, railroads and trains. All of those things: the great expanse, bridges, railroads, small town post offices, they give me a sense of stability. I know, kind of strange.

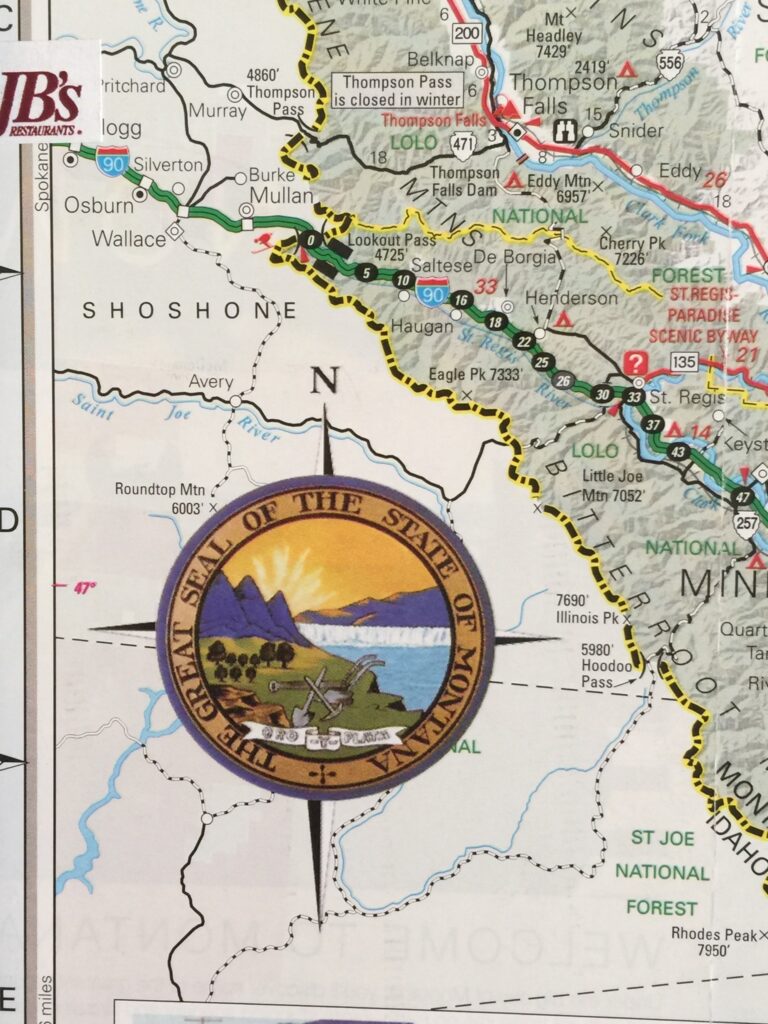

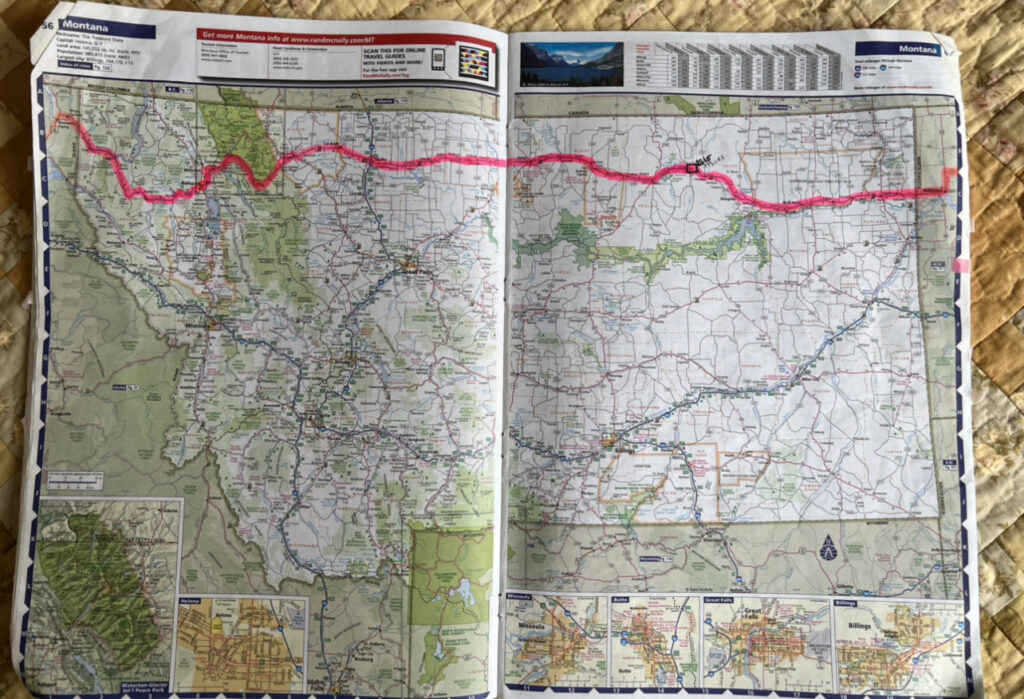

I remember Williston, North Dakota, because we had a conversation about blue collar jobs, the oil industry and fracking. It was raining lightly as we crossed into Montana and my dad welcomed me to big sky country. I didn’t get it until the clouds dispersed, and then it blew me away as it brightened up. We covered ~800 miles from Willmar and rested in Saco. My dad loved it there. It wasn’t even a town—just a bar with an apartment above it and a motel beside it that ran alongside green fields and, of course, a railway. I was swarmed by mosquitos on a short run along the tracks.

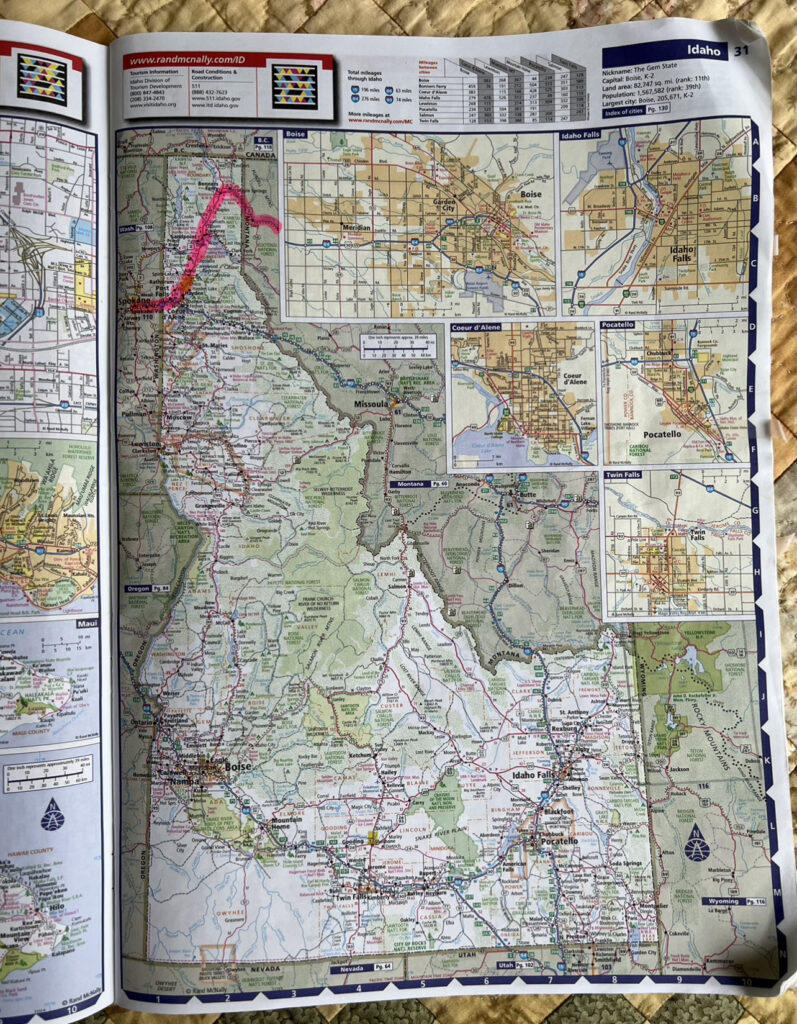

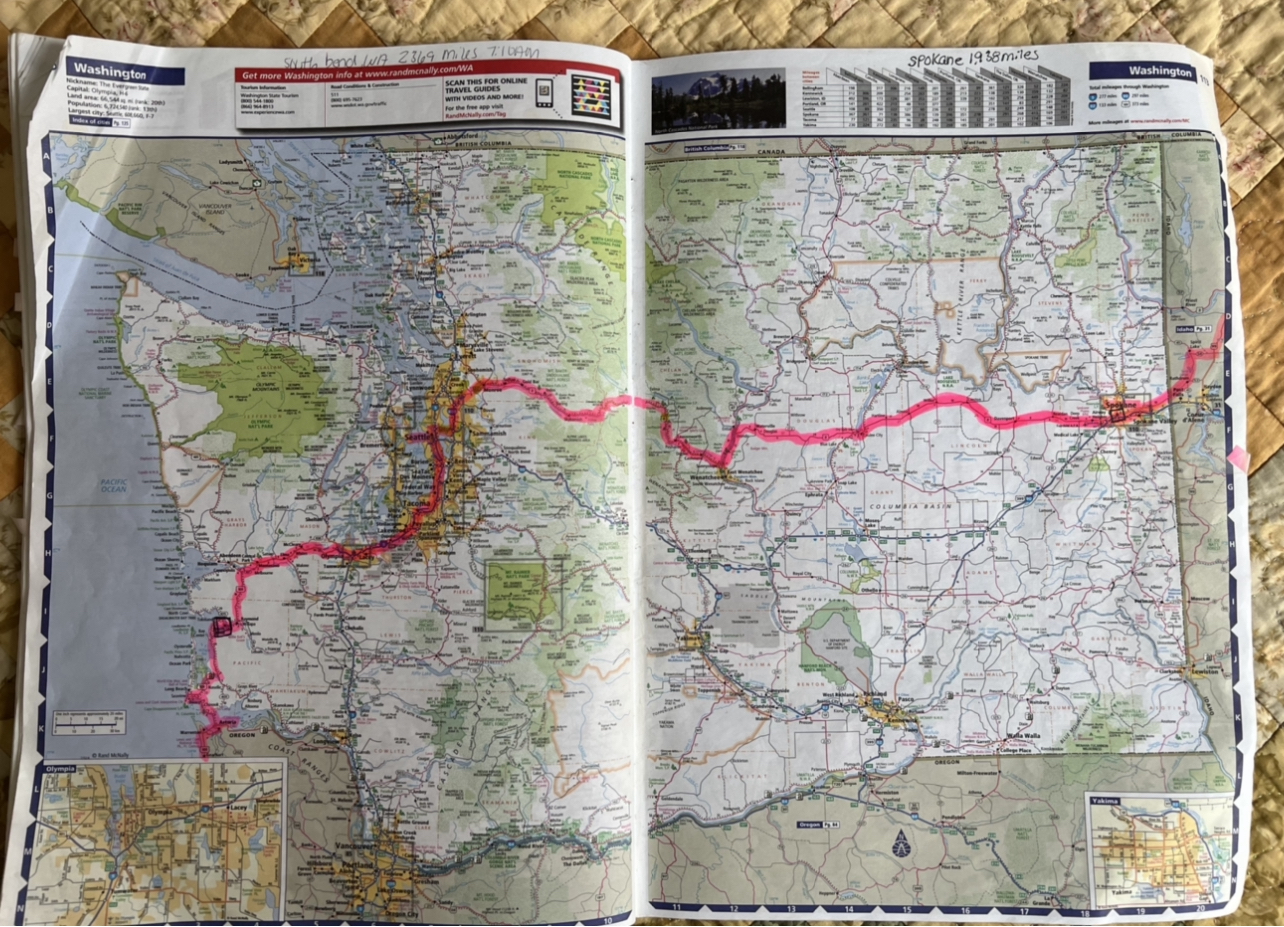

On day three, we drove from Saco to Spokane, Washington, crossing through 50ish miles of Idaho at the top of the state. I feel like until you drive through Montana the description of big sky country is incomprehensible. Added to that, the suspense of driving from the flat and big sky to foothills and then to a mountain range is unreal. It feels like you’re approaching the range forever because you don’t see it until you see it and then it still takes so long to get there, but then it’s right there. We went right through a part of Glacier National Park and hiked a bit. Seeing my dad in those elements felt so charming and I think fulfilling because we were in my element and out of his. I loved it. And again, the trains and railroad trusses weaving along the edge of the mountain was enchanting.

Crossing from Montana to and through Idaho was a trip. The eastern side had the greenest green trees and bluest blue lakes. I’d never see such a stark contrast in natural colors right up against each other. We stopped and I jumped into water that felt and looked like it could grant new life. I could have just lived right there outside of Sand Point.

I know why my dad wants to move to the middle of nowhere. It’s got an enticing pull, to live near the wild and nothing. Maybe someday I’ll disconnect and do it. Just get lost and find home along some mountain with fresh views and an edge of danger.

That night, after a day of breathtaking views over the course of ~600 miles, was my least favorite. After stopping at a place to eat at the edge of Idaho we continued on and spent the night in Spokane. We had been in all these nowhere places and all of a sudden we were in a city.

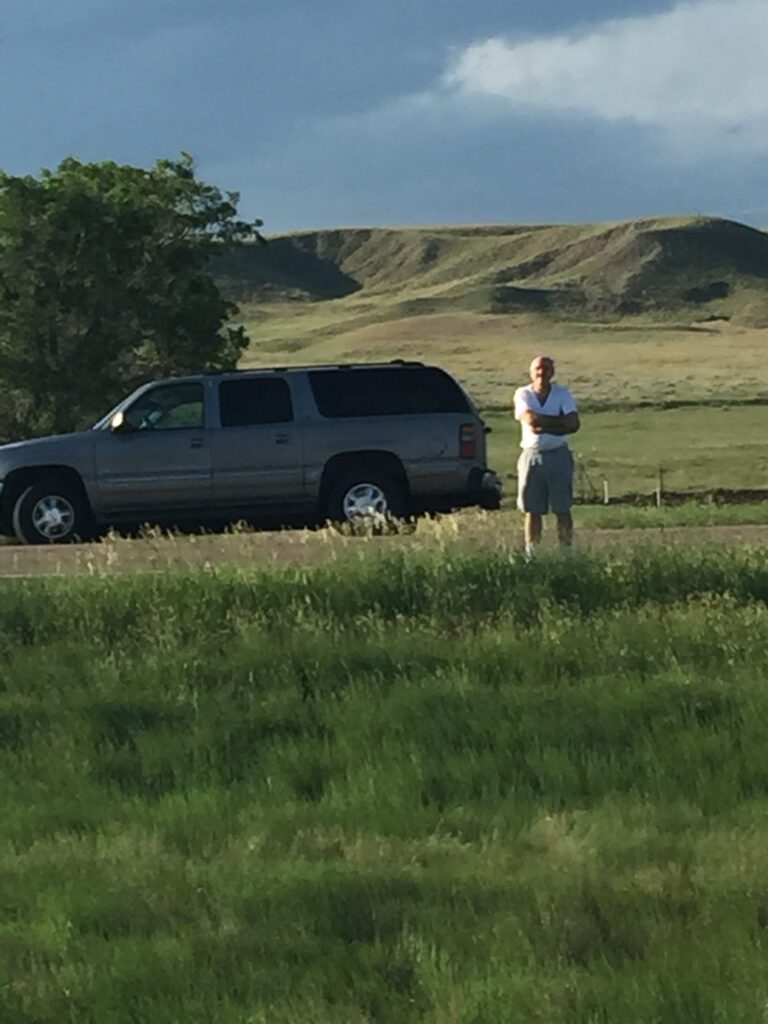

We drove across Washington state on day 4. Even after all the landscape changes, the one that surprised me the most was learning that the eastern part of Washington is actually flat. It’s full of wheat fields. We parked alongside the road to observe and take it in. I have this photo of my dad just inspecting the land—it’s one of my absolute favorites. It’s a moment I caught him fully taking in everything around him that he’d never seen—that we’d never seen—together. I’m like him like that. When I have a feeling and I am outside I’ll stop and let myself feel it fully. I breathe in the wind and taste it, feel it on my skin, watch for it to move things around me even lightly and listen to everything that I can. He did that there.

The landscape changes quickly. Somewhere before Stevens Pass there’s this big valley that is so steep to get into we were on our breaks the entire way down. The grade was a bit terrifying, but the basin was full of life. We reveled in the freshness of the apples and the cherries as a snack to take on the road while approaching the Cascade mountain range and headed up.

As we climbed, we were on sweeping multiple lane roads that brought us through and around the mountain. It felt like we were moving way too fast as locals passed us without hesitation. On that wide and winding road we were level with both the top of pines to our right over the edge, and then the bottom of pines to our left as we hugged the mountain. It was unreal.

We spent some time in Seattle around the space needle, and then we hit the road until we came to this little place called South Bend. I think this was the most memorable night. We were there in the early evening and we ate at this little bar on the Pacific. We learned a bit about the town, how it floods easily and such. My dad sparked up a conversation with a man next to us and they got to talking about oyster farming. It turned out the man owned a boat docked next door in the bay. We learned that people buy land in the ocean for oyster farming the same way you would buy a field for a crop of corn or soy. He walked us through the three million dollar boat and showed us how it works. My dad listened intently. It’s one of the things I’ve grabbed from him and respect so much. The man knows so many different things because he’ll talk with strangers in nonsense places that end up granting him a look at the world from a view he’d never have got if he kept to himself. It’s a memory I cherish, and a knack I hope to keep as I grow—to talk with strangers in grand places, obsolete places and nonsense places.

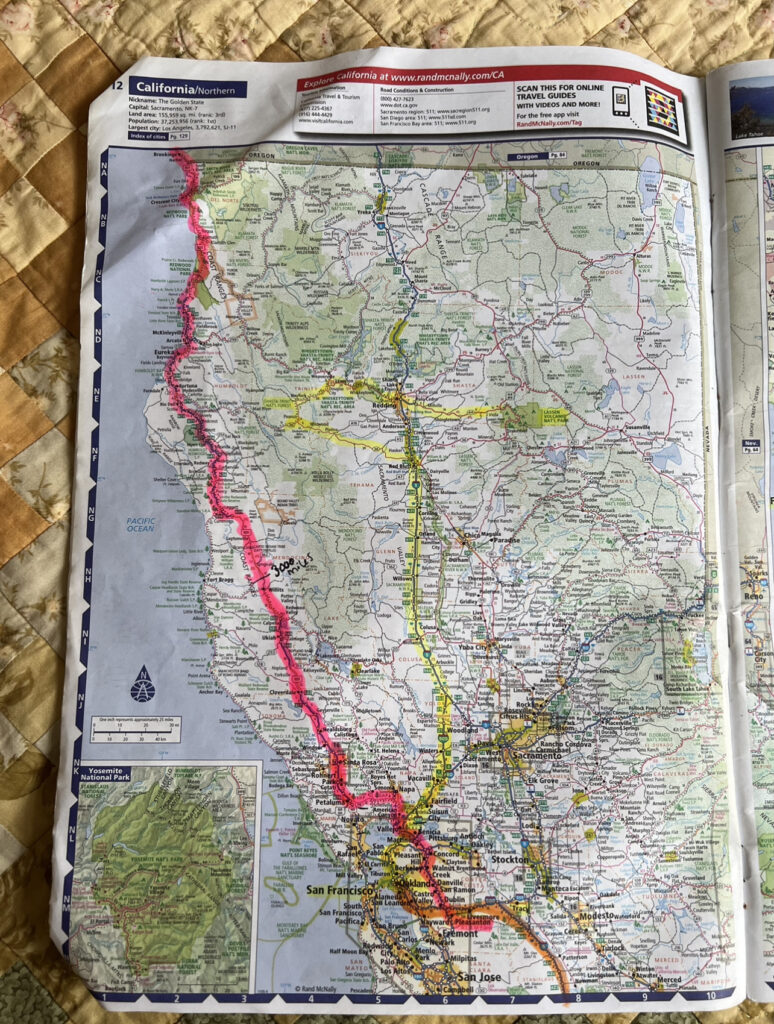

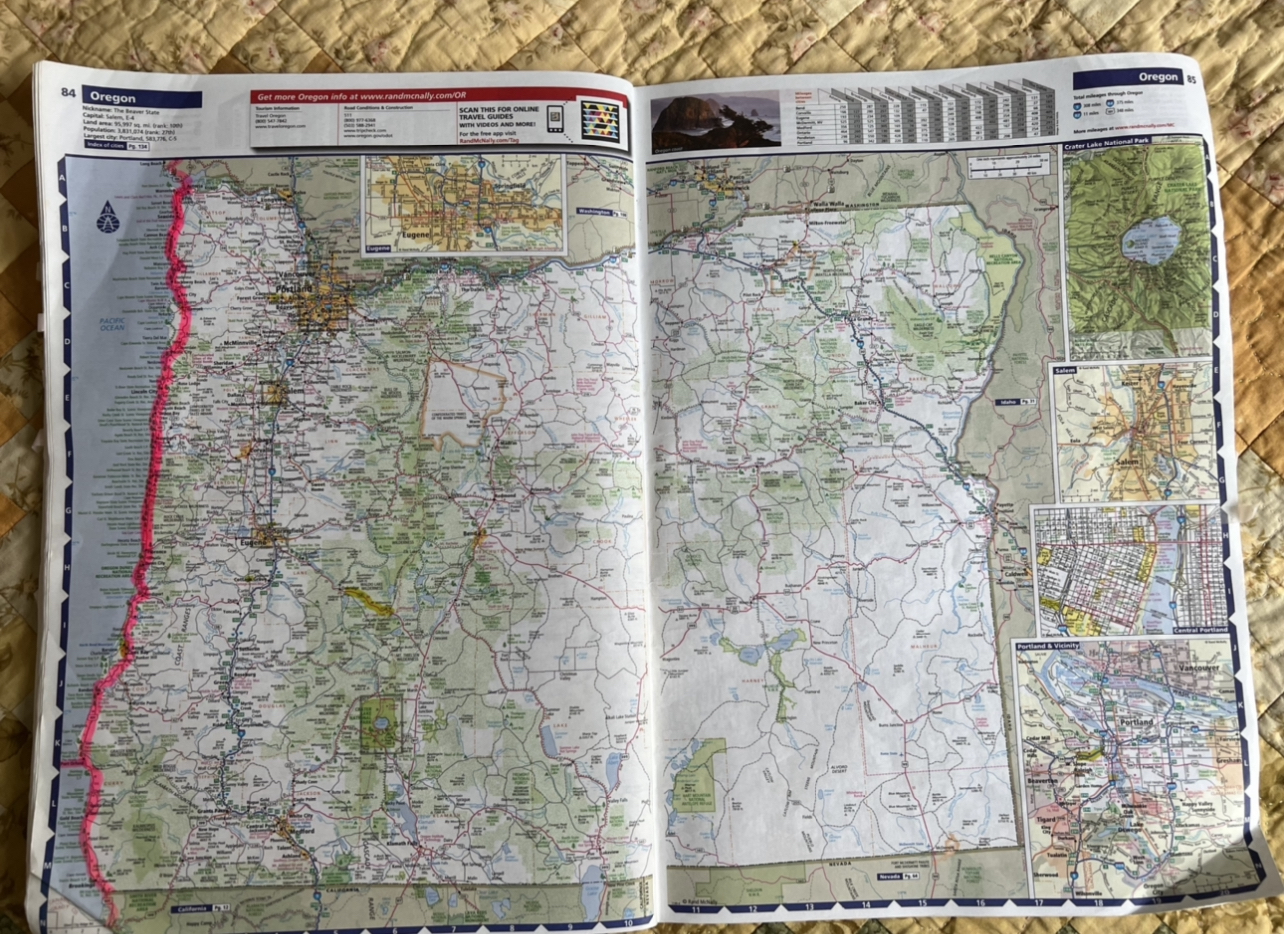

The next morning we stopped at a bakery in Astoria, Oregon. It was the first real sense I got of what I was moving to on the West Coast—a total change of pace and style from Wisconsin, Michigan or Iowa. It takes about eight hours to drive the Oregon coast, and the 101 is the absolute most stunning route I’ve ever been on. Oregon in general makes me have a sense of how small I am. I was doing this little thing where I was kind of laughing but afraid but my jaw was just dropped in amazement of the route.

Once we crossed into California we left the coast and hit the red woods. We stayed in Eureka, I think, but that’s the only night I didn’t recored mileage from the odometer. It was a really strange night and we stayed at an uneasy rundown little place. We were up early and reached the 3,000 mile mark on the last day of our trip shortly before Willits. We stopped there to visit my good friend and wrestling partner from college.

We had a half-day drive ahead of us yet and I think the stop prompted some thoughts about my wrestling career for him. He inadvertently questioned, or I guess maybe wanted to make sure about, my decision to take the corporate job. The decision was filled with excitement, but it was paralleled with pain.

From 2010-12 I wrestled at the U.S. Olympic Education Center in Marquette, Michigan. I trained and traveled internationally as I worked toward my dream of pursuing the Olympics. My dad knew my goal and supported it. I had made the Junior Pan Am team in 2011 and wrestled in Sao Paulo, Brazil. In 2012 we learned that the USOEC women’s freestyle program would close at the end of the year. We had just got back from a training camp in Japan. I was feeling really strong going into the last chance qualifier for the 2012 Olympic Team Trials. I lost the last spot to Jenna Burkert, my teammate at the time who is now a world bronze medalist, and placed second at Olympic Team Trials for this quad leading to Tokyo. Jenna was also the person that beat me in 2011 for the Junior World Team, which is why I wrestled at Pan Ams. Shortly after OTT in 2012 I blew out my shoulder in a practice match and had to go home for surgery that summer after the USOEC shut down. The entire sequence of events changed my wrestling career.

I transferred to Waldorf and turned my pursuit to a college national title. I had to rehab the entire 2012-13 season, and then the 2013-14 season was an entire year of getting over the fear of hurting my shoulder again. It wasn’t until after placing in the All-American rounds at nationals that year that I just in a flip of the switch was over it. I wanted to win. I was back training the following Monday in the hunt for a title my senior season of 2014-15. I prepped all summer and wrestled like it all season. I think I was ranked #4 headed into the national tournament but I was in contention for the title and I knew it. So, when I didn’t win it was absolutely heartbreaking. I gave everything I had to academics and wrestling in Iowa. I did things right and I trusted in the hard work. But I lost. It felt like I choked, really. There were some other things that went into the decision after closing the season, but I took the job in finance shortly after the national tournament. I separated myself from wrestling, knowing full well I could train for another year and give Olympic Team Trials a shot in 2016.

What my dad said was simple—he didn’t ask me why I chose the job in finance, he said something along the lines of, “I’m surprised you didn’t move to Colorado and keep trying to make the Olympics”. He knew my heart as well as I did. He knew how painful it was. I cried some silent tears then with my feet on the dashboard, and I cried just now writing these sentences. But that was it. That was all he said. And with that, I closed my wrestling career and connection to the community for several years.

We drove all the way to Pleasanton that day. It’s a little city thirty minutes from the Bay, and that’s where I lived for my first year in California. The apartment was nice. I had a view of the mountain out my second-story porch and a palm tree close enough to touch. All I had with me when I moved was a $316 dollar check from my last pay period from Subway where I worked as the assistant manager. When we got there my dad took me to target for some groceries and other kitchen essentials. He bought me a bike to ride to work, handed me a couple hundred dollars in cash, gave me a big hug and then he was gone.

I was alone. In a new place. With a new life. A yoga mat to sleep on. And it was time to start over.